By 2069, every single person on Earth will have access to the Internet. This is because Google, Facebook, and a few other competitors are using Internet connectivity initiatives as a mechanism to economically “colonize” developing countries and the rural outskirts of the world. Not a single person will be deprived of the opportunity to have miserable experiences on social media and feel overwhelmed by information overload.

In all seriousness, access to the Internet’s unbelievable web of knowledge and services might be the biggest societal differentiator today. Making sure that everyone has a connection to the infinite health advice, education, financial leverage, ecommerce, etc. is practically a human right – it’s a moral duty. However, morality is not the motivator for the half dozen companies bringing the rest of the world online.

Over the next forty years, the companies who bring the Internet to the developing world and rural outskirts will position themselves in extremely lucrative positions. The implications associated with connecting the next 50% of the world is one of the most economically exciting opportunities we may see this century. It’s a long-term opportunity, that will take decades to show returns. However, it’s an investment that those with extra capital are jumping on.

Already a future thinker?

Then become a friend.

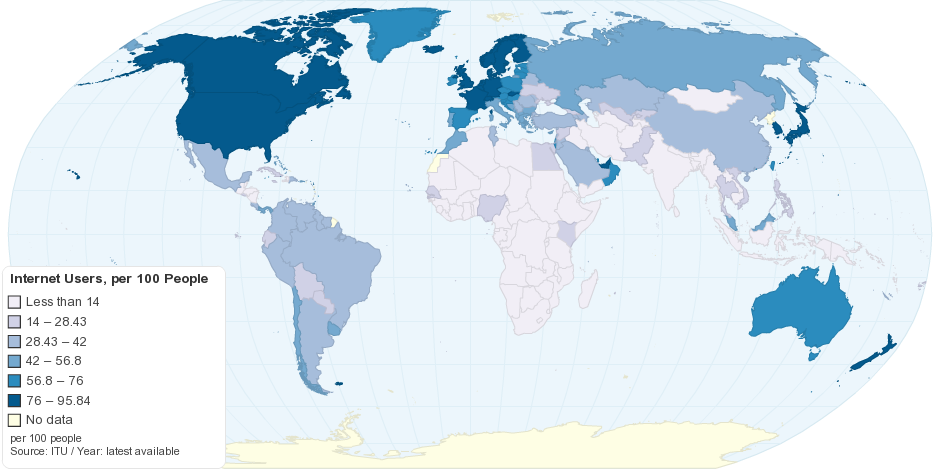

The Global Internet Numbers

2018 was a very special year for the Internet because we surpassed the 50/50 threshold for global Internet users. According to the International Telecommunication Union, 51.2% of the global population (or 3.9 billion people) are now using the Internet. And it only took about 30 years to do so. With 20% of the world population starting Internet usage in the last 8 years, you’d think that getting last half of the globe on would be a lot faster. Unfortunately, this won’t be the case.

The first half of the world was the easier to bring online. Connectivity swept through developed nations and other regions where high incomes, good education and dense urban centres smoothed the way. The second half is expected to be harder to hook up. Many places that remain offline are rural and remote where the costs of installing mobile internet towers and other infrastructure can be five times higher than in urban areas.

Ian Sample, The Guardian

In simple terms, it’s not very easy (nor financially responsible) to build a bunch of fiber connections to small villages in rural, mountainous Peru. Same goes for the vast landscapes of Africa and the arid lands of the Middle East. Not to mention, these aren’t lucrative economic markets in the short-term. That’s why you don’t have telecom providers champing at the bit to connect the other half of the globe. This image will give you a good idea of where the Internet is badly needed:

Regardless of the logistical nightmare of bringing the Internet to these places, the UN has projected we’ll reach universal Internet access (defined as 90% global population) by the year 2050. (By 2069, I predict that we’ll have reached 99%.)

How will we get there if not by telecom companies?

Big Tech Saviors

All of those above numbers mean one thing: economic opportunity. There are massive markets to be unlocked. And who has the resources, vision, and attitude to take over the world (ahem, I mean, attitude to help the world)?

The usual suspects: Google, Facebook, Elon Musk & SpaceX. Not Amazon this time, though.

Alphabet (Google) believes they can solve this problem at a very low cost through networks of balloons. Their Project Loon uses high-altitude balloons placed in the stratosphere at an altitude of about 18 km (11 mi) to create an aerial wireless network with up to 4G-LTE speeds. The balloons maneuver by adjusting their altitude and riding wind currents. And they’ve recently completed a crucial 6 balloon test project.

Facebook and their Aquila project is approaching this problem aerially as well. However, instead of balloons, they’re working with Airbus to develop better versions of what are known as high-altitude platform station, or HAPS, systems that can be built into aircraft for the purpose of beaming down high-speed internet. Since the network of flights is pretty consistent and at a massive scale, they’d be deploying this in a fairly efficient way.

And because it seems no two companies are thinking alike regarding this problem, SpaceX has a program known as Starlink which aims to provide universal broadband internet access to the world using a constellation of satellites (estimates upwards of 12,000 of them). Samsung and Boeing are looking at it the same way, as well as, Telesat Leo (a Canadian telecom company).

What do these companies all stand to benefit from this?

Perhaps the most lucrative reason all these companies are making this investment is that building this infrastructure will set them up with a huge business to charge others for access to their networks. Not to mention, the power of giving people their first Internet experience in and of itself will pay huge returns because it’s such an epiphanic experience.

Additionally, for Facebook and Google:

Getting billions more people online would provide a valuable new supply of eyeballs and personal data for ad targeting.

Tom Simonite, MIT Technology Review

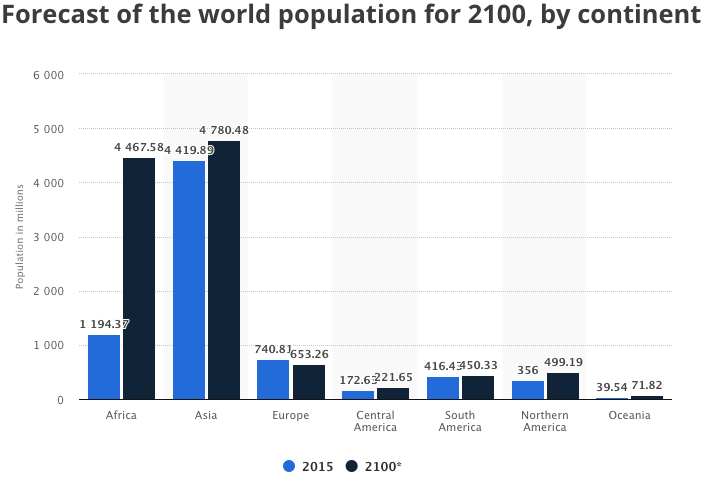

This is especially true when you look at the entire continent of Africa, which is clearly the most underserved in terms of Internet access. Along with that, they’re also on a population trajectory like none other:

Africa is projected to more than double their population by 2050 and nearly triple it by 2100. Unicef estimates that 4 out of every 10 people globally will be African by the end of this century. All the above companies are salivating at the economic opportunities that are going to emerge in African countries over this century.

Deploying in Africa is a lot easier said than done, since we’re talking about serving 54 different countries. Which means working with 54 different governments. And figuring out distribution on a case by case basis.

This is why we cannot discount some of the grassroots projects coming out of Africa such as BRCK, who designs rugged modems for harsh environments with limited connection and power. In other words, they are well-adapted for remote environments like Africa.

Anyways, as all of these global internet projects get underway, what are we looking at in the years leading up to universal Internet access and the year 2069?

A New Form of Colonization

There is no clear front-runner when it comes to onboarding the Internet-less population. The players involved all have significant resources, technology, and expertise – not to mention insane motives. All of this makes it seemingly impossible to think that a small fish could do anything significant here.

In this sense, it’s the new form of colonization. However, this time around the colonizers are corporations. It’s a race to colonize and solidify their presence in emerging markets the quickest.

And so goes the story of human history. Those with access to more advanced technology will use it to control those without it. The first to develop advanced seafaring technology (Dutch, English, Chinese) found themselves owning the oceans and therefore conquering new lands. The settlers of America used their gunpowder and muskets to obliterate the natives. This is a story that has repeated itself throughout human history. And I don’t think it won’t happen again.

Yes, all these “colonized” people are getting the Internet (a beautiful invention) out of the deal. However, it won’t necessarily be the Internet we know here in America where there’s a lot of freedom (whether that freedom is actually there or just perceived).

They’ll get the Internet in the way Google wants them to sees it, where everything revolves around search, YouTube, and collecting as much data about the user as possible in exchange for free services. Or maybe they’ll get the internet the way Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg wants them to see it where they’ll simply be another node for connecting the world and the goal is to get you locked-into using all the different services Facebook provides.

At one point, 67 human rights groups signed an open letter to Zuckerberg that accused Facebook of “building a walled garden in which the world’s poorest people will only be able to access a limited set of insecure websites and services.”

Jessi Hempel, Wired

He [Zuckerberg] argued that a limited internet was better than no internet; if people couldn’t afford to pay for connectivity, “it is always better to have some access and voice than none at all.”

Another big problem is that it’s a matter of the powerful exerting the power. Google, Facebook, and others with money are “strong-arming” the competition.

Technology is not the only thing keeping 4.3 billion people offline, though. For example, policies in India mandate that telecom companies provide coverage to poor as well as rich areas, but the government hasn’t enforced the rules, says Sunil Abraham, executive director of the Centre for Internet and Society, a think tank in Bangalore.

Tom Simonite, MIT Technology Review

He is also wary of Project Loon because of the way Google and other Western Internet companies have operated in developing countries in recent years. They have cut deals with telecoms in India and other countries to make it free to access their websites, disadvantaging local competitors. “Anyone coming with deep pockets and new technology I would welcome,” he says, but he adds that governments should fix up their patchy regulatory regimes first to ensure that everyone—not just Google and its partners—really does benefit.

In the year 2069, there won’t be a single person left unconnected by the Internet. The Internet will be a vastly different landscape, in a way we cannot predict now.

If we look back to 1969, AT&T and RCA were the technology titans spearheading the connectedness of the world. Neither of which are major players in this new age of connectedness.

Everything you know about this new environment called the Internet pales in comparison to what it will be fifty years from now. The companies who rule it today may not exist in 2069 or they may have reached a level of power unseen by human history.