When science and the humanities collide, it’s usually a battle of existential proportions. However, this time the disparate communities came together to make a major statement (and a few dollars).

Last week, the high-brow auction house Christie’s sold a painting called Portrait of Edmond

Well, it was created by a machine learning algorithm. That’s right. Its creator was an AI network!

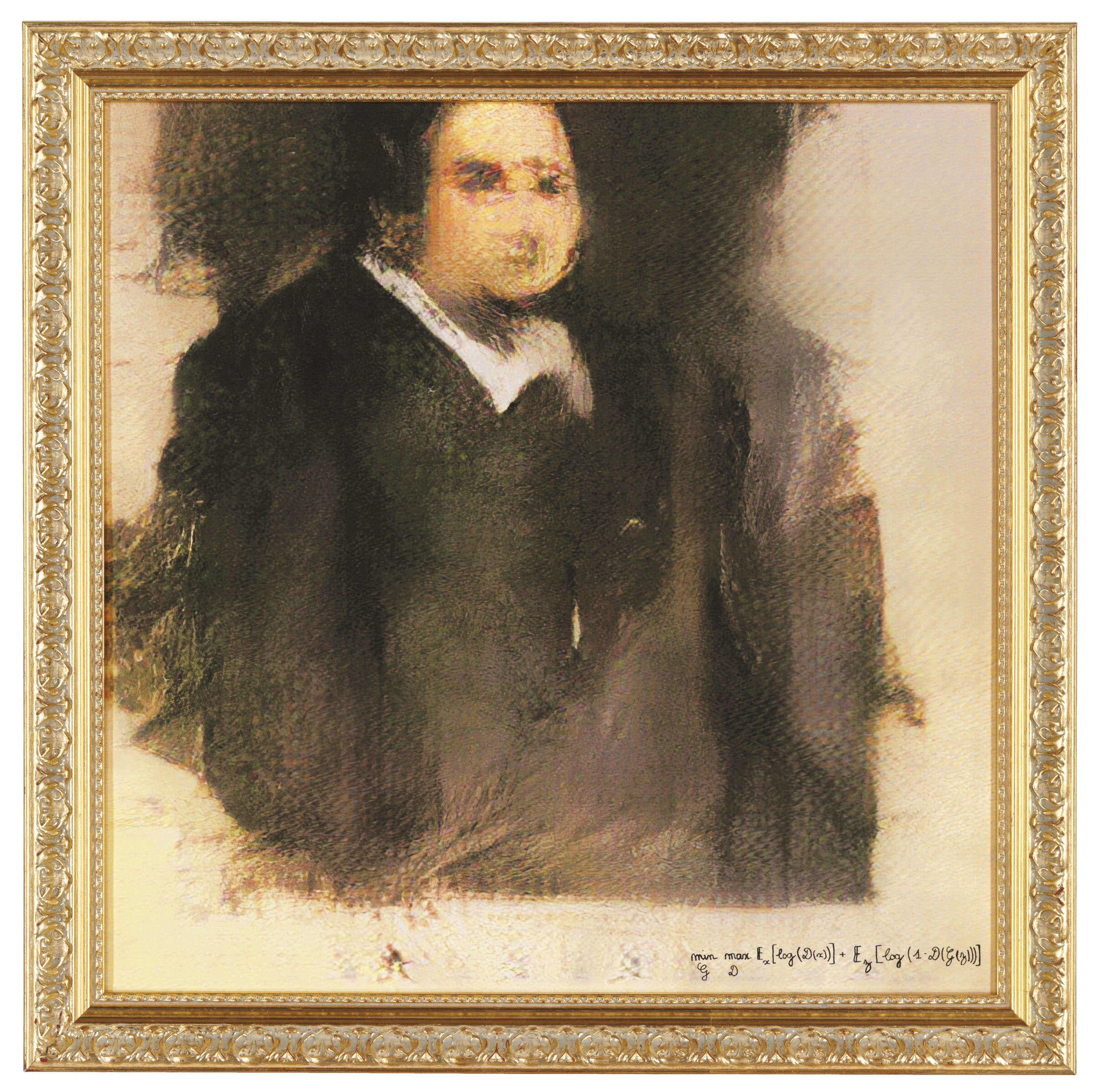

The team behind the algorithm, an artist collective called Obvious, trained the AI network on thousands of portraits from the 14th to 20th centuries – teaching it how to replicate and refine portraits of its own (you can read about the process here and their help from the open-source community). The result looks unfinished and unsettling. But, I’ll let you decide if it’s your style or not:

Now, I want to make this perfectly clear that this does not mean computers can be creative. In fact, the marketing of this painting was a little misleading. AI-generated art is far from an autonomous process. There’s still a heavy amount of human intervention required.

You can draw a parallel between AI-generated art and art class for 10-year-olds – where an art teacher walks them through each step and occasionally intervenes to make sure it’s not a total disaster.

Regardless, this is still a momentous event. More than anything, it’s a sign of acceptance – that perhaps the art community is ready to explore the artistic medium of artificial intelligence. It’s very possible that the anonymous buyer, who paid 45 times the estimated price point, likely saw this as a “Bitcoin moment” and could signal a surge in algorithmic art auctioning.

Skilled algorithmic artists like Robbie Barrat and Mario Klingemann will be ready to cash in on this movement. Although, is algorithmic art truly art?

Already a future thinker?

Then become a friend.

Art Without Intention

A few months ago I got into a Twitter debate with a very respected technologist, Benedict Evans. His argument (and the argument of many other doubters) is:

If we’re defining a machine’s intent against how humans have intent (through consciousness), then Ben is correct. AI will not create art until we achieve Artificial General Intelligence (AI that can think for itself).

Isn’t it possible, though, that we should define intent differently for machines? Perhaps machines have intention through specific prompts and lines of code. In this case, then AI is highly capable of creating true art (and already has).

Another way of thinking about this argument around intent is the way we consume artwork.

There are of course critics and consumers that are just as interested in understanding what Picasso was mentally experiencing while painting The Old Guitarist as they are interested in the painting itself. This is Ben’s argument of “intent” being crucial to art.

On the other hand, there’s the notion that we must separate the “art” from the “artist” before consuming a piece of art. Otherwise, we’ll analyze the artist instead of the artwork. In other words, “Who cares who the artist is? This work moves me and inspires my thoughts.” In this case, intent doesn’t matter.

These two schools of thought will likely argue the definition of AI-created art for a long time to come. Yet, I do believe they will agree about one major thing…

A Revolution in AI Assistance

We’re entering an era where artists of all kinds will be extremely empowered by artificial intelligence tools. The ideation, refinement, and distribution phases will all have significant AI applications to help artists produce more quality work and reach the audiences that desire their style.

Artists are constantly asked, “Where do you get your ideas from?” It’s a tough question to answer because the ideation process is generally intangible. However, researchers are finding ways for computers to augment the early creation phases of 3D objects. This is one instance of an algorithmic artist creating a prompt for a human artist to later fill in. I can imagine an AI-plugin for Photoshop that analyzes an artist’s style and can inspire that artist by prompting them with the first few random lines or textures of a new piece of art. Sometimes the first lines are the hardest part – a part of the creative process that AI may be able to solve.

Refining and editing one’s artwork is an equally important part of the creative process. In the music industry, we’ve already seen huge progress from companies like LANDR which provide musicians with an AI that’ll master their raw tracks. In visual art, Color-Correct is one early example of machine learning that helps clean up photographs. We’ll likely see many more applications that assist artists with their editing process.

And of course, when it comes to distribution, social media is one instance of AI helping artists reach their fans. However, we’ll likely see improvement upon the AI in distribution to help artists identify potential markets and opportunities.

All artistic disciplines are in for large-scale interference from AI tools in the next decade. Savvy artists that embrace this change will find themselves pushing the boundaries of human creation.