23andMe, and all of its DNA sequencing

But, in their 13 years of existence, they’ve encountered countless controversies and added to the black, white, and gray areas that these massive databases of genetic data embody.

The Effect on Individuals.

The Golden State Killer went undiscovered for some 40 years until one of his distant relatives spit in a tube for some DNA sequencing company and then criminologists tracked this lead through GEDMatch which would eventually lead them right to his door. Following this incident, people began having worries about personal privacy (even though this was a great thing that happened). Shortly after, this news came to light:

Family Tree DNA, one of the largest genetic sequencing companies in the space, announced that they’re allowing the FBI’s Investigative Genealogy Unit to access their expansive archive of genealogical data to track down criminals.

Taking a DNA ancestry test may put you on the FBI’s radar

Although Family Tree DNA is largest of all the companies to openly cooperate with police and investigators, it still felt like the whole genome sequencing industry was a commercial front for Big Brother. Of course, it’s not. And users can opt out of familial matching, which would remove them from FBI searches.

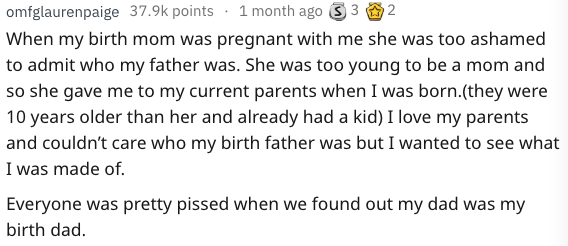

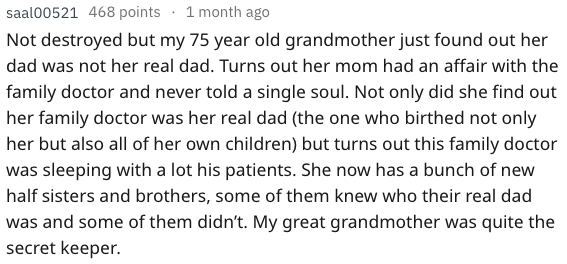

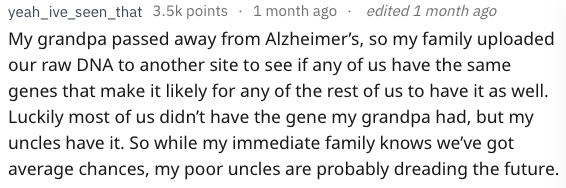

Honestly, the true investigational impact these DNA tools have had are within family units. If you take a DNA test, then you need to prepare yourself to possibly uncover some family secrets, as these Redditors found:

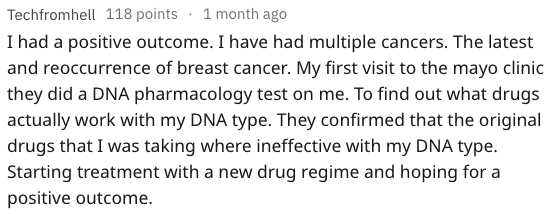

It’s been such a common occurence to take these tests and have shocking truths uncovered that Facebook groups and foundations, such as the NPE Fellowship, have been formed to help people cope. It’s not all bad, though. In some cases, these tests have brought forth a silver-lining:

It’s evident that 23andMe, along with their competitors, exist in this gray area where we cannot say for sure whether they’re bringing promise or pain to the world.

One blatant problem that’s bubbling up is that DNA sequencing sites are eliminating the anonymity of sperm donors. Currently, the only thing protecting the confidentiality of individual donors is the threat of legal action

“I wrote her and said, ‘Hi, I think your son may be my daughter’s donor. I don’t want to invade your privacy, but we’re open to contact with you or your son,’” she recalled. “I thought it was a cool thing.”

Jacqueline Mroz, New York Times

Not only was Danielle met with hostility and disappointment, but the sperm bank reached out to her with threats of legal action and $20,000 in potential penalties.

Couple the widespread use of DNA sequencing with the emerging abilities of facial recognition algorithms to recognize the similarities in the faces of distant relatives and we’ll literally disintegrate any trace of genetic anonymity on the planet.

Donor anonymity will suffer the same fate as the cassette tape.

Jacqueline Mroz, New York Times

These are just some of the unforeseen consequences of this rise in DNA sequencing companies. Honestly, we, the individuals providing our data, aren’t even the people necessarily benefiting.

Already a future thinker?

Then become a friend.

The Effect on Big Business.

23andMe, in July of 2018, announced a four-year partnership with GSK, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies. For $300 million, GSK is allowed exclusive access to 23andMe’s genetic database, for the purpose of “research and development of innovative new medicines and potential cures.”

This means that 23andMe customers will, in effect, be charged twice for any potential “innovative new medicines” their DNA helps produce. The first time they paid for the DNA sequencing service; the second time they pay for the medicine that it helps create. A more equitable solution, according to Peter Pitts, the president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, would be to pay 23andMe customers for their genetic data when it is used in research.

Daniel Oberhaus, Motherboard

Daniel brings up a good point, that there’s a little bit of monetary double-dipping in this situation. I wouldn’t be surprised if his idea for user compensation gains some steam.

On a more philanthropic note, Bill and Melinda Gates megaphoned how useful genetic data will be to the medicine and health community:

By looking at more than 40,000 samples voluntarily submitted by 23andMe users, scientists discovered a potential link between preterm labor and six genes—including one that regulates how the body uses a mineral called selenium. The 23andMe study (which our foundation helped fund) found that expectant mothers who carry that gene were more likely to give birth early. Researchers won’t know until later this year how exactly the mineral affects preterm birth risk. But if the link proves substantial, selenium could one day be a cheap and easy solution to help women extend their pregnancy to full term.

Bill & Melinda Gates 2019 Annual Letter

All of the preceding examples were unforeseen use cases of this genetic data. They may not have been unforeseen to people within those companies, but they definitely were to most users before they gave away their data. Undoubtedly, there are going to be many, many more use cases to come. Hopefully, most will fall along the lines of Bill and Melinda Gates’ vision for this data.

I don’t have a clear answer whether or not to go forward with getting your DNA sequenced. Definitely think twice and talk with your immediate and extended family about it because your genetic test will affect them too.

This Friday, March 1st at

We’d really love you to join us (digitally) for lunch as we discuss this prescient topic. You can reserve your seat by clicking the link below: